The Legality of Private Investigators Searching Discarded Trash: A Comprehensive Legal Analysis

1. Introduction: The Landscape of Privacy and Investigation

This report provides a comprehensive legal analysis concerning the circumstances under which private investigators (PIs) may lawfully search discarded trash. The discussion navigates the complex interplay between federal constitutional protections, state-specific privacy statutes, and the fundamental distinction between the authority granted to government agents and that afforded to private citizens. The objective is to offer precise, actionable insights for private investigators operating within these legal boundaries, while also informing individuals about their privacy rights regarding discarded materials.

The legality of examining discarded trash is not a straightforward matter. It involves nuanced interpretations of core legal concepts such as privacy, the abandonment of property, and the scope of governmental versus private authority. A thorough understanding of these distinctions is essential for any party seeking to operate within the confines of the law, whether conducting an investigation or asserting privacy rights.

2. The Fourth Amendment: Foundation of Privacy Protection

The Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution serves as a cornerstone of individual liberty, safeguarding individuals from “unreasonable searches and seizures” of their “persons, houses, papers, and effects”.1 Its fundamental purpose is to protect an individual’s inherent right to privacy and ensure freedom from unwarranted governmental intrusion into their personal lives and property.2

The concept of a “search” within the context of the Fourth Amendment is triggered when a governmental employee or agent intrudes upon an individual’s reasonable expectation of privacy.2 The landmark Supreme Court decision in

Katz v. United States (1967) established a two-pronged test to determine whether such an expectation exists and has been violated.3 First, the individual must exhibit a personal, subjective expectation that the place or activity in question is private; this implies that the person must behave in a manner that indicates a desire for privacy.4 Second, and crucially, this subjective expectation of privacy must be one that society is prepared to recognize as “reasonable” or “legitimate,” an objective standard reflecting societal norms and values regarding privacy.3

Katz significantly expanded the scope of the Fourth Amendment, famously stating that it “protects people, not places,” thereby eliminating the requirement of physical trespass for a search to occur and extending protections to intangible interests like conversations.3

As a general rule, warrantless searches of private premises are presumed to be “per se unreasonable” under the Fourth Amendment.2 For a search warrant to be issued, it must be based on “probable cause,” supported by an oath or affirmation, and must “particularly describ[e]” the place to be searched and the persons or things to be seized.2 This particularity requirement is designed to prevent general, exploratory rummaging.6 However, several “specifically established and well-delineated exceptions” permit warrantless searches. These exceptions include situations involving consent, searches conducted incident to a lawful arrest, exigent circumstances (such as imminent danger, the imminent destruction of evidence, or a suspect’s imminent escape), items in plain view, and searches of abandoned property.2

The Fourth Amendment’s fundamental limitation to governmental action is a pivotal principle for understanding the operational scope of private investigators. This constitutional safeguard is explicitly designed to curtail intrusions by the state, encompassing federal agents and state police.2 This is more than a mere definitional point; it is the foundational legal distinction that fundamentally differentiates the operational constraints placed upon private investigators from those imposed on law enforcement. If a private investigator is not deemed an “agent of the government,” then the entire elaborate framework of warrant requirements, probable cause, and the reasonable expectation of privacy, as developed under the Fourth Amendment, does not directly apply to their investigative activities. This establishes the core premise for understanding the legal leeway private investigators possess, while simultaneously underscoring that other general laws, such as those prohibiting trespass, will still bind them. This distinction frames the subsequent discussion by setting the stage for why private investigators operate under a different set of rules compared to police.

3. Trash and the “Reasonable Expectation of Privacy”: The California v. Greenwood Precedent

The landmark U.S. Supreme Court case, California v. Greenwood (1988), serves as the seminal authority governing privacy rights concerning discarded trash at the federal level.1 The Court unequivocally ruled that law enforcement officers can legally search trash that has been placed at the curb for public collection without needing a warrant.1 Crucially, any incriminating evidence discovered during such a warrantless search is considered admissible in criminal prosecutions.1

The rationale behind the Greenwood ruling rests on several key pillars. First, the Court held that by placing trash at the curb for collection, individuals are deemed to have “abandoned” it, thereby relinquishing any reasonable expectation of privacy in its contents.1 Second, a significant component of the Court’s reasoning was the concept of public availability and access. Trash left for collection is readily accessible to “members of the public, including children, animals, scavengers, [and] snoops”.1 The Court concluded that police are not required to disregard evidence of criminal activity in trash that any member of the public could have observed.1 Even if the trash is placed in opaque bags, the “common knowledge” of its public accessibility negates a reasonable expectation of privacy.10 Third, the act of placing trash at the curb effectively transfers it to a third party—the trash collector. The Court reasoned that individuals possess no legitimate expectation of privacy in information or items they voluntarily turn over to a third party.1

Despite its enduring legal impact, the Greenwood decision faced significant criticism. Some legal commentators argued that the ruling effectively “trashed” the Fourth Amendment by failing to recognize a reasonable expectation of privacy in the “telling items Americans throw away”.10 Justice Brennan, in his powerful dissent, eloquently articulated that “scrutiny of another’s trash is contrary to commonly accepted notions of civilized behavior” and that a “single bag of trash testifies eloquently to the eating, reading, and recreational habits of the person who produced it,” revealing intimate details about sexual practices, health, finances, and personal relationships.13

The underlying principle of Greenwood is not merely about the general concept of “abandoned property,” but rather hinges critically on the doctrine of “public accessibility.” The Court’s detailed explanation of its decision emphasizes that the core justification for allowing warrantless searches of curb-side trash lies in its exposure to the public and its transfer to a third party.1 This means that the Court’s reasoning was not simply based on whether the owner subjectively desired to abandon the trash, but rather on the objective fact that the owner had placed it in a public sphere where privacy could no longer reasonably be expected. The physical act of moving trash to the curb is the critical trigger, transforming its legal status from private to publicly accessible. This transformation removes Fourth Amendment protection for governmental searches. This understanding is vital for private investigators, as it defines the precise moment and location where a search becomes legally permissible for anyone, including private citizens, without directly violating the Fourth Amendment.

4. The Significance of “Curtilage”: Protecting Private Spaces

In the context of the Fourth Amendment, “curtilage” refers to the area immediately surrounding and intimately associated with a home, which is considered an extension of the private domain of the house itself.1 This area is understood to “harbor the ‘intimate activity associated with the sanctity of a man’s home and the privacies of life'”.14

Like the home itself, the curtilage is generally afforded robust protection under the Fourth Amendment against “unreasonable searches and seizures”.14 Consequently, police typically require a warrant to search trash or any other items located within the curtilage.1 The critical distinction for privacy purposes lies in the trash’s location. Trash left

by the curb for collection is considered abandoned and generally not protected by the Fourth Amendment, as established by Greenwood.1 However, if trash remains located

within the curtilage (e.g., inside a fenced yard, on a porch, or close to the house), it may retain a reasonable expectation of privacy and thus be protected.1

The U.S. Supreme Court, in United States v. Dunn, outlined four key factors to consider when determining the extent of a home’s curtilage.14 These include: 1) the distance from the home to the place claimed to be curtilage; 2) whether the area claimed to be curtilage is included within an enclosure surrounding the home; 3) the nature of use to which the area is put (e.g., if it is the site of domestic activities); and 4) the steps taken by the resident to protect the area from observation by passersby.14 It is important to note that an officer, positioned in a place where they have a right to be (outside the curtilage), may generally look into the curtilage without performing a “search” if they are observing nothing more than any other member of the public could see.14 However, entering the curtilage generally requires a warrant or a recognized exception to the warrant requirement.14

The concept of curtilage introduces a geographical boundary to the Greenwood rule, creating a “safe zone” for privacy that even police cannot easily penetrate without a warrant. This area is not merely a technical legal boundary for law enforcement; it defines a physical space where society recognizes a significantly heightened expectation of privacy.14 While the Fourth Amendment’s direct application is to government action, this societal recognition of privacy within the curtilage has broader implications for any intruder, including private investigators. For PIs, this means that even though the Fourth Amendment’s warrant requirement does not directly apply to them, entering the curtilage to access trash would almost certainly constitute criminal trespass, a separate and distinct legal violation. Therefore, the curtilage effectively functions as a “no-go” zone for PIs seeking to search trash, making the

Greenwood “curb” rule the primary, if not sole, legally permissible avenue for a PI’s trash search without risking criminal charges. This highlights that the legal boundaries for PIs are not solely defined by constitutional law but also by general criminal and civil statutes.

5. Private Investigators vs. Government Agents: A Crucial Distinction

The fundamental protection offered by the Fourth Amendment against unreasonable searches and seizures is specifically designed to limit intrusions by the government, encompassing federal agents and state police.2 Consequently, searches conducted by purely private individuals generally do not fall under the direct purview of the Fourth Amendment.8

A critical exception to this general rule arises if a private individual is deemed to be “acting as an instrument or agent of the government”.8 This typically occurs when law enforcement directs, encourages, or participates in a warrantless search conducted by a private party. If such an agency relationship is established, the private individual’s actions are then treated as state action, and the Fourth Amendment’s protections apply. Any evidence obtained in violation of the Fourth Amendment in this context could be deemed inadmissible in court.8 Conversely, if the private party acts “completely on their own accord,” without any government direction or involvement, police and prosecutors could potentially use any evidence found, even if law enforcement themselves would have needed a warrant to obtain it. The U.S. 11th Circuit Court of Appeals case,

United States v. Perez, provides a helpful illustration of these rules.8

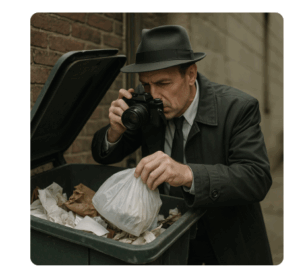

Private investigators, by definition, are private citizens. Their legal authority is generally identical to that of any other private citizen; they do not possess the special powers vested in law enforcement officers, such as the power of arrest beyond a citizen’s arrest, or the authority to execute search warrants.15 While PIs are “not bound by some of the restrictions that courts and legislators have placed on law enforcement,” it is equally true that they “don’t get any of the special powers that cops get, either”.17 PIs are strictly bound by general criminal laws and civil statutes. This includes, but is not limited to, avoiding trespass on private property.17 Illegally entering a home, vehicle, or locked receptacle to access trash, even if unlocked, would constitute burglary or a similar criminal offense.17 Many jurisdictions require PIs to be licensed, with varying requirements that can include specific experience, educational qualifications, examinations, criminal history reviews, and even character references (e.g., Massachusetts requires three character references).15 These licensing requirements imply a regulatory framework governing their professional conduct. PIs are professionally obligated to maintain detailed notes of their investigations and must be prepared to testify in court regarding their observations.16 Regarding trash specifically, a “trash hit” (the act of taking trash from the curb) is generally considered legal for PIs, as the property is deemed abandoned and in a public space under the

Greenwood precedent.17 Some PIs even employ techniques like swapping out trash bags to avoid detection, though this tactic does not alter the underlying legality of the initial taking.20

The “agent of the state” doctrine represents a significant strategic risk for private investigators. While PIs generally operate outside the direct constraints of the Fourth Amendment, any perceived collaboration, direction, or even close coordination with law enforcement could transform their private actions into government actions. If this transformation occurs, any evidence obtained through warrantless searches, such as trash searches, could be challenged as a Fourth Amendment violation and potentially rendered inadmissible in court. This dynamic compels PIs to maintain strict operational independence from law enforcement if their investigative findings are intended for legal proceedings where Fourth Amendment protections are relevant, such as criminal defense cases. This highlights a crucial strategic decision for PIs: the closer they align with law enforcement, the greater the risk that their evidence might be suppressed due to constitutional violations.

Furthermore, the fact that the Fourth Amendment’s direct constraints do not apply to PIs does not grant them unlimited investigative powers. Private investigators are still subject to general criminal laws, such as those prohibiting trespass or burglary.17 This points to a crucial multi-layered legal reality: while federal constitutional law might not directly constrain a PI’s search of trash, state criminal and civil laws, including those pertaining to trespass, privacy torts, or even theft (depending on the specific circumstances and state interpretation of abandoned property), do. This means a PI’s permissible actions are bounded by a complex interplay of indirect federal constitutional principles, through the “agent of the state” doctrine, and direct, enforceable state statutory and common law.

| Feature / Actor | Law Enforcement (Police) | Private Investigator (PI) |

| Primary Governing Law | Fourth Amendment (U.S. Constitution), State Constitutions, State Statutes | State Statutes (Trespass, Privacy Laws), Common Law, Licensing Regulations |

| Warrant Generally Required? | Yes, for areas where a reasonable expectation of privacy exists (e.g., inside a home, curtilage), unless a specific exception applies. | No, the Fourth Amendment’s warrant requirement does not directly apply to private citizens. |

| Probable Cause Needed? | Yes, probable cause is a prerequisite for obtaining warrants and for many warrantless searches. | No, the Fourth Amendment’s probable cause requirement does not directly apply to private citizens. |

| Reasonable Expectation of Privacy (REP) | REP is constitutionally protected; searches violating REP without a warrant or valid exception are unconstitutional. | REP is not a direct Fourth Amendment constraint on PIs; however, PIs must still respect other privacy laws (e.g., avoiding trespass). |

| “Agent of the State” Doctrine | N/A (they are the state). | Crucial exception: If a PI acts at the direction of or in concert with law enforcement, their actions may be considered state action, making the Fourth Amendment applicable. |

| Evidence Admissibility (Federal Courts) | Evidence obtained in violation of the Fourth Amendment is generally inadmissible under the Exclusionary Rule. | Evidence obtained by a PI acting independently and lawfully (without trespass, etc.) is generally admissible, even if law enforcement could not have obtained it directly without a warrant. |

| Legal Authority | Possess special powers granted by law (e.g., arrest, search, seizure with warrant/probable cause). | Generally possess the same authority as any private citizen (e.g., citizen’s arrest); do not have special police powers. |

| Primary Constraints | Constitutional limits (Fourth Amendment), statutory law, case law, internal police procedures. | Statutory law (e.g., trespass, harassment, theft), civil liability for privacy torts, state licensing board regulations, professional ethics. |

6. State-Specific Legal Considerations: The Massachusetts Example

It is a fundamental principle of American constitutional law that while federal law, such as the Greenwood precedent, establishes a minimum baseline for privacy protections, individual states retain the sovereign authority to provide greater privacy protections under their own state constitutions or statutes.1 This means a state can impose stricter requirements on searches than those mandated by the U.S. Constitution.

Massachusetts has its own robust privacy provision, Article 14 of its Declaration of Rights, which closely parallels the Fourth Amendment. It states, “Every subject has a right to be secure from all unreasonable searches, and seizures, of his person, his houses, his papers, and all his possessions”.21 The Supreme Judicial Court (SJC) of Massachusetts has, at times, interpreted Article 14 to offer broader privacy rights than the U.S. Constitution’s Fourth Amendment.5 Consistent with federal law, Massachusetts courts, such as in

Commonwealth v. Krisco Corp., have held that if trash is left on the curb for collection, individuals relinquish all expectations of privacy, and police can freely search its contents without a warrant. The pivotal factor remains “the degree to which the garbage at issue was exposed, or accessible, to the public”.21

Crucially, an expectation of privacy does exist in Massachusetts when trash is located closer to the dwelling, specifically “within the ‘curtilage'” and “not accessible to the public”.21 The

Commonwealth v. Straw (1996) case is highly significant in Massachusetts jurisprudence, providing a clear example of how state law can diverge from federal precedent.22 In

Straw, the court ruled that a defendant who threw a closed and locked briefcase from a window into the fenced-in curtilage of his family’s home had not abandoned it for privacy purposes.22 The court strongly reaffirmed that the curtilage of a home enjoys “full Fourth Amendment protection” (referring to the equivalent protection under Article 14) and that the defendant’s action was “entirely, and more persuasively, consistent with an intent to deprive the police of access to the briefcase while not precluding his own later reclamation”.22 This decision explicitly highlights that merely discarding an item does not automatically relinquish privacy rights if the item remains within a constitutionally protected area and the owner’s intent to protect privacy can be inferred.22 The court also rejected the prosecution’s argument of exigent circumstances, finding that once the briefcase was under police control, any exigency ceased, and a warrant should have been obtained.22 As a result of the illegal search, the evidence found in the briefcase and the defendant’s subsequent admissions were suppressed under the “fruit of the poisonous tree” doctrine.22

The contrast between the federal Greenwood standard and Massachusetts’ Article 14, particularly as interpreted in Commonwealth v. Straw, demonstrates a critical legal principle: state constitutional interpretations can indeed establish a “higher floor” of privacy protection than federal constitutional law.22 This is a crucial nuance often overlooked when only federal precedent is considered. For private investigators, this means that while a “trash hit” at the curb is generally permissible nationwide due to

Greenwood, accessing trash within the curtilage might be explicitly illegal under state law, even if the Fourth Amendment (federal) does not directly apply to them. This underscores the absolute necessity for PIs to be deeply knowledgeable about and adhere to the specific laws of the jurisdiction in which they operate, as a federally permissible action might constitute a state-level crime. While the Greenwood rule permits PIs to search curb-side trash federally, PIs operating in Massachusetts must be particularly cautious about trash located within the curtilage. Massachusetts state law, as interpreted in Straw, provides a higher degree of protection for such areas. Trespassing into curtilage to access trash would be illegal and subject to criminal penalties. Massachusetts also has general privacy laws 23 and specific regulations governing PIs 24, including requirements for character references during the licensing process 15, underscoring the state’s regulatory oversight.

| Factor / Condition | Federal Law (Police Search, per Greenwood) | Massachusetts Law (Police Search, per Krisco/Straw) | Private Investigator (General Federal Rule) | Private Investigator (Massachusetts Specific) |

| Location: At Curb for Collection | Not protected; No reasonable expectation of privacy. Warrantless search permissible. 1 | Not protected; No reasonable expectation of privacy. Warrantless search permissible. 21 | Generally permissible; Not subject to Fourth Amendment. Must avoid trespass to access the curb. 17 | Generally permissible; Must avoid trespass to access the curb. 17 |

| Location: Within Curtilage (e.g., fenced yard, close to home) | Protected; Reasonable expectation of privacy. Warrant generally required for police search. 1 | Highly Protected; Reasonable expectation of privacy. Warrant generally required. Intent to protect privacy is key (Commonwealth v. Straw). 21 | Not permissible (likely criminal trespass); PI has no special authority to enter private property. 17 | Not permissible (likely criminal trespass); Stronger state privacy protection reinforces this, making it a clear legal boundary. 17 |

| Owner’s Intent (e.g., concealing vs. abandoning) | Implied abandonment by placement at curb, regardless of subjective intent to hide contents. 10 | Explicitly considered; Throwing into fenced curtilage not abandonment if intent to protect privacy from police exists (Straw). 22 | Not directly relevant to Fourth Amendment non-applicability, but intent to conceal on private property implies trespass if accessed. | Highly relevant; Intent to protect privacy within curtilage reinforces trespass and potential privacy law violations, making it a higher risk. 22 |

| Third-Party Access | Voluntary exposure to trash collector (a third party) negates privacy expectation. 1 | Similar principle applies for public access areas. 21 | PI acts as a private citizen, not a third-party collector; access must be lawful (e.g., not trespassing). | Same. |

| Evidence Admissibility | Admissible in court. 1 | Admissible if lawfully obtained (e.g., from curb); Inadmissible if obtained from curtilage without warrant (Straw). 22 | Generally admissible if PI acts independently and lawfully (no trespass, etc.), as Fourth Amendment does not apply. 8 | Generally admissible if PI acts independently and lawfully, but the higher bar for “lawful” access (especially within curtilage) means greater risk of inadmissibility if state laws are violated. |

7. Practical Implications and Best Practices for Private Investigators

For private investigators, understanding the legal landscape surrounding trash searches is critical for lawful and effective operation.

Permissible Actions for PIs Regarding Trash:

A private investigator can generally and lawfully search trash that has been placed at the curb for public collection.17 This is permissible because, under federal law, such trash is considered abandoned property with no reasonable expectation of privacy, as established by

California v. Greenwood.1 Similarly, if trash is located in a dumpster or other receptacle in a clearly publicly accessible area, such as a public park or a commercial dumpster not situated on private property, it is generally considered permissible for a PI to examine, provided there are no specific state or local ordinances prohibiting rummaging, scavenging, or theft. To ensure that any evidence gathered is admissible in court and to avoid potential Fourth Amendment challenges, private investigators must operate strictly independently. They should not act at the direction, request, or under the supervision of law enforcement.8

Impermissible Actions for PIs Regarding Trash:

Private investigators are strictly prohibited from entering private property, including the curtilage of a home (such as a fenced yard, garage, or porch), to access trash without explicit consent from the owner or legal occupant.1 Such an act would unequivocally constitute criminal trespass, a serious offense.17 Furthermore, illegally entering a home, a vehicle, or a locked trash receptacle to access discarded materials constitutes burglary or a similar criminal offense, regardless of whether the Fourth Amendment applies.17 PIs must also be acutely aware that some states, like Massachusetts, may offer greater privacy protections for trash than federal law, particularly if it is located within the curtilage and the owner has taken steps to maintain privacy.1 Ignorance of these state-specific nuances is not a valid defense. While surveillance from public property is generally permissible, any investigative actions that cross the line into harassment, stalking, or other forms of intimidation are illegal and can lead to criminal charges or civil lawsuits.

Ethical Considerations and Professional Conduct:

Most jurisdictions require PIs to be licensed and adhere to specific professional codes of conduct.15 Strict adherence to these regulations is crucial for maintaining licensure, avoiding disciplinary action from state boards, and upholding professional integrity.19 PIs are expected to maintain meticulous records of their investigative methods, including precisely how and when trash was accessed. This detailed documentation is essential, especially if the findings are intended for legal proceedings, as PIs must be prepared to testify credibly about their observations.16 PIs must exercise “great care… to remain within the scope of the law” to avoid incurring criminal charges.16 The line between legal investigation and illegal activity can be thin, and crossing it carries severe consequences. While the law may permit certain actions, PIs should always consider the ethical implications of their methods. As highlighted by the

Greenwood dissent, rummaging through trash is inherently intrusive and reveals highly personal information.10 Professional ethics often extend beyond mere legal compliance.

The practice of conducting a “trash hit,” where a private investigator collects trash from the curb, is widely considered a legally viable tactic.17 This practice is a direct consequence of the

Greenwood ruling’s principle of abandonment for publicly placed trash. However, the strong dissenting opinions in Greenwood and the inherent nature of trash revealing “intimate details” about an individual’s life highlight a significant ethical tension.10 While legally permissible for a PI, it remains a highly intrusive act that delves deeply into personal habits, health, and financial information. This indicates that legal permissibility does not automatically equate to ethical desirability or broad public acceptance, and private investigators must carefully navigate this perception in their professional practice.

The legal liability spectrum for a private investigator is multi-layered. PIs are largely immune from direct Fourth Amendment challenges unless they are deemed “agents of the state”.8 However, this immunity does not extend to other legal frameworks. PIs are fully subject to state criminal laws, such as those prohibiting trespass and burglary 17, and can face civil liability for privacy torts. Furthermore, their professional licenses are governed by state regulatory boards 15, which can impose sanctions for unethical or illegal conduct, even if it does not result in criminal charges. This demonstrates that a PI’s legal exposure is multi-layered, meaning that avoiding one type of legal issue, such as a Fourth Amendment violation, does not grant immunity from others. A holistic understanding of this spectrum of liability is crucial for responsible and lawful investigative practice.

8. Conclusion: Navigating the Legal Complexities

The analysis of when a private investigator can lawfully search discarded trash reveals a nuanced and complex legal landscape. The Fourth Amendment primarily restricts governmental action; thus, private investigators are generally not bound by its warrant requirements unless they operate as “agents of the state.” Trash placed at the curb for public collection is typically considered abandoned, losing its reasonable expectation of privacy under federal law, as established by California v. Greenwood, making it generally permissible for PIs to search.

However, trash located within the “curtilage” of a home, such as a fenced yard or the immediate vicinity of the house, retains a higher expectation of privacy and is constitutionally protected. Private investigators are legally prohibited from trespassing onto private property to access such trash, as this would constitute a criminal offense. Furthermore, state laws can provide greater privacy protections than federal law, as vividly illustrated by Massachusetts’ Article 14 of the Declaration of Rights and the Commonwealth v. Straw decision, which offer stronger safeguards for trash within the curtilage. Beyond constitutional considerations, private investigators must always operate within the bounds of general criminal laws, such as those prohibiting trespass and burglary, and strictly adhere to state-specific licensing and ethical guidelines to avoid legal repercussions and professional sanctions.

The legal landscape for private investigators searching discarded trash demands careful consideration of federal constitutional precedent, specific state laws, and the crucial distinction between private and governmental action. While the curb-side “trash hit” is generally permissible, any intrusion onto private property or perceived collaboration with law enforcement carries significant legal risks for the PI and the admissibility of any evidence obtained.

Disclaimer

This report provides general legal information for educational purposes and should not be construed as specific legal advice. Individuals and private investigators are strongly advised to consult with a qualified legal professional regarding their specific circumstances and the applicable laws in their particular jurisdiction.

Works cited

- Can Police Legally Search Your Trash Left by the Curb? | Roth …, accessed July 5, 2025, https://www.rothdavies.com/criminal-defense/frequently-asked-questions-about-criminal-defense/searches/can-police-legally-search-your-trash-left-by-the-curb/

- Fourth Amendment | Wex | US Law | LII / Legal Information Institute, accessed July 5, 2025, https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/fourth_amendment

- Katz and the Reasonable Expectation of Privacy Test | U.S. Constitution Annotated | US Law, accessed July 5, 2025, https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution-conan/amendment-4/katz-and-the-reasonable-expectation-of-privacy-test

- What Constitutes a Search Under the Fourth Amendment? – Roth Davies LLC, accessed July 5, 2025, https://www.rothdavies.com/criminal-defense/frequently-asked-questions-about-criminal-defense/searches/what-constitutes-a-search-under-the-fourth-amendment/index.html

- Fourth Amendment–Further Erosion of the Warrant Requirement for Unreasonable Searches and Seizures: The Warrantless Trash Searc – Scholarly Commons, accessed July 5, 2025, https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=6598&context=jclc

- Particularity :: Fourth Amendment — Search and Seizure – Justia Law, accessed July 5, 2025, https://law.justia.com/constitution/us/amendment-04/09-particularity.html

- Abandoned Property – Doc McKee, accessed July 5, 2025, https://docmckee.com/oer/procedural-law/procedural-law-section-4-2/abandoned-property/

- Does the Fourth Amendment Apply to Private Individuals? – Baez Law Firm, accessed July 5, 2025, https://www.baezlawfirm.com/does-the-fourth-amendment-apply-to-private-individuals/

- California v. Greenwood | EBSCO Research Starters, accessed July 5, 2025, https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/law/california-v-greenwood

- California v. Greenwood – Wikipedia, accessed July 5, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/California_v._Greenwood

- Is evidence found in trash cans admissible in court? | The Law Office of Jeffrey Jones, accessed July 5, 2025, https://www.lawjj.com/blog/2025/02/is-evidence-found-in-trash-cans-admissible-in-court/

- California v. Greenwood | 486 U.S. 35 (1988) – Justia U.S. Supreme Court Center, accessed July 5, 2025, https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/486/35/

- Trash, Thermal Imagers, and the Fourth Amendment: The New Search and Seizure – SMU Scholar, accessed July 5, 2025, https://scholar.smu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1822&context=smulr

- www.scbar.org, accessed July 5, 2025, https://www.scbar.org/media/rd0axygv/curtilage.pdf

- Private investigator – Wikipedia, accessed July 5, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Private_investigator

- The Private Investigator, accessed July 5, 2025, https://www.mypspa.org/article/more/the-private-investigator

- Guide to Private Investigator Laws Governing PI Work: Are Private Investigators Legal?, accessed July 5, 2025, https://privateinvestigatoredu.org/private-investigations-laws/

- Chapter 4749 – Ohio Revised Code, accessed July 5, 2025, https://codes.ohio.gov/ohio-revised-code/chapter-4749

- Frequently Asked Questions – Private Investigator (PI), accessed July 5, 2025, https://www.bsis.ca.gov/consumers/faqs/pi.shtml

- Trash Theft Exposed: A Private Investigator’s Unconventional Methods – YouTube, accessed July 5, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eSop50GvZmE

- When Can Police in Massachusetts Search Your Trash for Evidence …, accessed July 5, 2025, https://jrmccarthy-law.com/2024/02/05/%F0%9F%97%91-when-can-police-in-massachusetts-search-your-trash-for-evidence/

- COMMONWEALTH vs. MARLON A. STRAW. :: :: Massachusetts …, accessed July 5, 2025, https://law.justia.com/cases/massachusetts/supreme-court/volumes/422/422mass756.html

- Massachusetts law about privacy – Mass.gov, accessed July 5, 2025, https://www.mass.gov/info-details/massachusetts-law-about-privacy

- OFFICE OF THE INSPECTOR GENERAL 945 CMR 1.00: RULES OF PROCEDURE Section 1.01 – Mass.gov, accessed July 5, 2025, https://www.mass.gov/doc/945-cmr-1-rules-of-procedure/download

- BOARD OF REGISTRATION OF HAZARDOUS WASTE SITE CLEANUP PROFESSIONALS 309 CMR 4.00 – Mass.gov, accessed July 5, 2025, https://www.mass.gov/doc/309-cmr-4-rules-of-professional-conduct/download

- A Guide to the Massachusetts Public Records Law – Mass.gov, accessed July 5, 2025, https://www.mass.gov/files/2017-06/Public%20Records%20Law.pdf

27. Private Investigator Ethics: The Essential Guide to Good Morals

Private Investigators vs Police : Understanding the 7 Key Differences

https://hubsecurityandinvestigativegroup.com/wp-admin/post.php?post=4035&action=edit